Winning Strategies & Racing Mindset

Mindset and race strategy can compliment your training by preparing you to choose the best scenario on race day. Having a “good day” for your race can be helped by a number of things.

We help our athletes train for their goals (we provide training plans and coaching), but on race day these intentional items give an edge to the thoughtful athlete.

(PS- Join our free community for resources, discount codes, insider news, and more!)

Mindset

Cultivating a successful mindset is a little more than just closing your eyes and thinking positive thoughts (although not terribly much more!).

- To start, predetermine your goals. (Shout out to Rod Wortley for instilling this one in us!)

- The goal you know you can achieve on any day (achievable goal)

- The goal you’ve been training for and can realistically achieve (believable goal)

- The goal you believe is possible on a perfect day (ultimate goal)

- “Run” the race in your head.

- If you know the course, “run” it in your head.

- If you don’t know it, imagine common scenarios. Imagine overcoming every obstacle. These might include hills, “hitting the wall,” being passed, and a long finish.

- Breathe deeply and release tension as you’re mentally “running.”

- Go over your goals. You must believe them.

- Train with your race in mind.

- Mindset is practiced while you train day in and day out.

- Imagine your race during harder workouts.

- Treat yourself like the runner you want to be during the race: proper form (stop slouching), positive self talk, and activating your muscles. (More on that here)

And always remember to enjoy your training. Savor the experience of running with partners, the serenity of a solo run, and the strength of your body as you gain fitness.

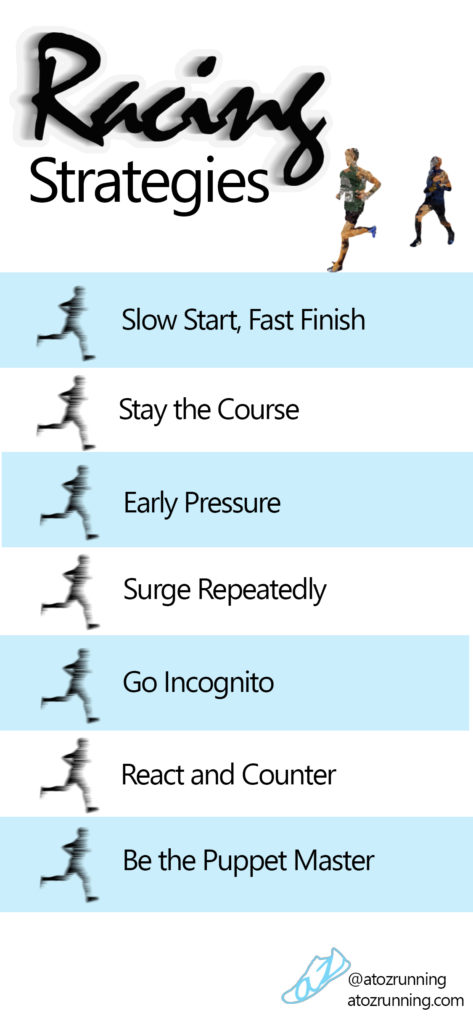

Race Strategies

Here begins a bit of a divergent path. What follows is a short list of common strategies you might employ in a race, but which ones and at what time you might employ them depends entirely on your goals and the context of the race itself.

I will try to explain concisely.

Consider first strategies to perform well in general. Whatever your level of competitiveness, if your goal is simply to finish in the fastest possible time for your current fitness, here are the top recommendations.

Slow start, fast finish. (George’s favorite!)

The Idea: start conservatively, build over time, finish strong

Risk vs. Reward: low risk, high reward

This is the classic negative-split approach to racing. The theory is good across nearly all distances (certainly mile and up). Lydiard is known to have captured the concept in simple terms: save 50% of your available energy for the last 25% of the race. The idea, then, is not to slog it out for a while. You simply ration your energy for the first 75% of the race so that you’ve got a big box of colorful tricks to toss about for the final quarter.

There’s a chance I could come up with over 100 examples of Olympic medals won by those employing this strategy. Similarly, any weekend racer will usually find a higher degree of success employing such a strategy.

Stay the course.

The Idea: start on pace, check in around half-way

Risk vs. Reward: low-medium risk, medium-high reward

For many, the early stages of a race prove unpredictable. Some days you feel it, some days you don’t, and much of the time, that initial feeling is totally wrong. There’s good sense to trusting your training and setting out on the target pace however you feel. At least for half the race distance. By then, you’ll have a better idea of whether the feeling you once felt way back in the beginning of the race was legitimate or the byproduct of race jitters that you left too long in a hot car.

Shifting considerations a moment, let’s address strategies to beat someone. Winning the race and beating the doddering fool beside you are not always the same thing, but there’s a decent amount of crossover. The key idea I want to isolate, here, is that these strategies only truly matter if the person you are trying to beat is also trying to beat you.

Early pressure.

The idea: go hard early and sustain for a substantial period of time

Risk vs. Reward: high risk, high reward

Contrary to the sound wisdom illustrated above, this strategy is all about making your opponents hurt more than they want to during the early stages of a race. Even if we don’t realize it, most of us have a ceiling regarding how fast we are willing to run in the first little bit of a race. When someone else exceeds that ceiling, most simply let them run away. It takes a conscious decision often with extreme cognitive dissonance to say, “A’ight, dude. I’ll take you on.”

That’s what makes it a brilliant strategy! If you can bluff well enough, you can take advantage of your opponents’ potential comfort line and create a sense of defeat or submission in them early in a race. Many struggle to recover from that, even when the common sense in the back of their minds tells them that there’s a good chance it’s a bluff.

So on that note, you kind of have to be willing to run most if not all of the race alone. If they do catch you, the whole system might backfire and give them even more confidence than before.

Remember, this is not strictly limited to those attempting to win the whole race (obviously a small minority of the thousands running the race). This applies to anyone attempting to race anyone else.

And by the way, I can once more give you several examples of how this has worked at the world class level despite the fact that many athletes in the field could have run the time if only they would have stayed with the crazy bloke who slammed the pedal down right out the gate.

Surge repeatedly.

The idea: throw down and sustain bursts throughout the race

Risk vs. Reward: medium-high risk, medium-high reward

Once again, this strategy is intended to take advantage of your opponents’ comfort zone. We all like to settle into a familiar pace and hang out as long as possible. Thus, when some sneaky blighter spins his wheels at a terribly inconvenient time in the race, it’s infuriating.

Even worse, if he does it again a short bit later, it becomes a nuisance. The crazy thing, though, is that if you do it enough (and don’t blow your legs up in the process), one very likely outcome is that you are going to shred the nerves of your competition.

Go incognito.

The Idea: stay as invisible as possible as long as possible

Risk vs. Reward: low risk, medium reward

Those two above are both designed around the idea that you want to attract attention. One problem with that is that if your competition knows you, they may also know whether you’re bluffing. If so, the head games you are trying to play won’t help.

Finding a pack and hiding out until the late stages of the race allow you to hold your hand close and drop your cards at more opportune moments, like a late-race surge that no one sees coming or a final stretch kick like a blazing star rising from the fog of ambiguity.

And sometimes it’s nice to just hang back and watch the show for a while.

React and counter.

The Idea: let someone else make the move, then counter it

Risk vs. Reward: medium risk, medium reward

It’s really just the classic duck and weave. If you want to take someone down, let him/her stick the neck out first, then take your swing. Some call the idea “covering the move.” That speedy devil over there creeping ahead? Slide in line and narrow the gap.

The beauty of the strategy, then, is in the counter. Most of us feel really good about ourselves when we start surging ahead of our opponent, but think back on a time when that very same opponent surged back a short time later. Your once wind-swept sails start luffing a bit? Mine do. That’s how I know the strategy works.

Be the puppet master.

The Idea: create the race you want

Risk vs. Reward: low risk, high reward

Here’s the truth about racing: it’s nearly impossible to actually prove that any given strategy actually helped a person achieve a given result. So many other factors contribute to something like physical performance, especially in longer distances. We can synthesize as many past races as we want and draw various conclusions, but most of it lacks any real proof of concept beyond circumstance.

Therefore, the one most clear point that can be made is that whatever the race strategy, when the race goes to your liking and best suites your perceived strengths, you are more likely to succeed than when it doesn’t. So be the one pulling the strings, if possible, and make the race the one you want.

A brief example…

I’ll give one, and perhaps the most common example of racing strategy. In many of the shorter distances (like mile, 5k, 10k), certain athletes prefer either a fast, even race or a slow start, fast finish race. Those who prefer the former simply hit the gas and see who keeps up. The latter, though, is a bit trickier.

Enter Matthew Centrowitz in the 2016 Olympic 1500m final. A notoriously crafty racer, Centro, was known to prefer to let others do the dirty work so that he could steal the glory in a dream-shattering final lap kick that left most world class milers questioning the meaning of life. To deprive him of that, other savvy racers in the Olympic final opted for an early surge. Centro, never one to enjoy being bested, made the calculated move to overtake the lead and promptly slow down, effectively negating the attempt to apply pressure.

In most distance races, that ploy matters little because they could have simply tried again. But in the 1500m, real estate runs out quickly and things tend to get pretty crowded, making counter-moves quite challenging.True to his reputation, Centro manipulated the race right into his lap so that before long, the final lap loomed and he was in a prime place to mince the rest of the field with his pummeling kick and rocket home to a gold medal not won by an American in over a century (yes, you read it right: the last American to win gold in the Olympic 1500 before Centro’s 2016 win was Mel Sheppard in 1908).

Flexibility

(Not to be confused with actual structural mobility.)

The big question we all prefer to avoid is what to do when the plan catches fire and burns to elementally unrecognizable slag. No problem! Just fall back on a different plan. Racing strategies should be flexible.

Seriously, though. If you and I have learned one thing during our time as runners, it’s that things fall apart. Knowing that, if we still toe start lines betting the farm and two first cousins on a single race plan, we deserve the inglorious conflagration inevitably headed our way.

So here’s what you do:

- Use Rod Wortley’s 3-tier goal approach so that for every race, you have 3 acceptable outcomes (the believable goal to start, the achievable goal to fall back, and the ultimate goal to chase).

- Before the race, consider likely obstacles, when they might occur, and what you will do in response (especially for longer races).

- During the race, remind yourself early and often why you are doing the thing you are doing (it’s too easy to forget ourselves in the excitement or nerves and completely abandon our strategies and goals).

- Know your limits and when you need to make adjustments (this is only accomplished through smart training and preparation during which you intentionally work to discover and ultimately elevate those limits).

The best claim I can make about the idea of adapting or adjusting plans, especially in the tumult of a race is that every decision has consequences. Knowing those potential consequences and making informed decisions is imperative.

For any degree of competitiveness, that begins with knowing your fitness and understanding how your training has worked to prepare you for that race. It begins with the simple question of why, in racing much the same as training.

For training: Why am I doing this particular workout on this particular day in light of these particular goals?

For racing: Why am I making this particular decision at this particular moment in light of this particular goal?

If you have an answer to those questions at all times, you’re on the road to the kind of running career that you can truly enjoy and sustain indefinitely. Fine tuning your racing strategies can prepare you for many scenarios.

Our Personal Experience with Mindset and Racing

Recently, our brother-in-law, George Goad, won a half marathon in Saint-Esprit, Québec (congrats, Geo!). In chatting with him about the race, he noted that his strategy, executed quite effectively over the course of his running career, was to start conservatively then press later in the race for an overall negative split. After sharing that, he said, “Hey! You guys should write about racing strategies.”

So that’s what we did. If you found this post helpful, you can thank George for instigating it!

From Andi:

I have been a poor racer most of my running career. Until my late 20s I had a very hard time as a competitive athlete. I will not bore you with my whole history, but I had mental hurdles to overcome when it came to racing.

In middle school, I fiercely loved to race, and I had success to show for it. In high school, I feared to race, and I had anxiety to show for it. In college, I raced to meet expectations, and I had low confidence to show for it.

Throughout those early years, I had different degrees of success. But I can tell you that the highest highs were always when I was the most free from fear or anxiety. Why? Because my performance is deeply influenced by my mindset.

I used to see this as a weakness and really was frustrated by the way I was wired. As I have found healing from my past, I have begun racing free from the anxiety and fear that wore me down for so many years. Now, I am better able to use my mind and emotion to celebrate the strength and opportunity from my Maker.

From Zach,

Andi’s experience is one you hear a lot from young athletes, more now than ever. But it is not unique to aspiring amateurs. One of the most distinct differences between paid professionals and most of the rest of us is the attention given to competition mindset and strategy.

Without giving anyone away, I can confirm the fact that I once sat in a hotel room with a world-class marathoner while this person agonized over the influence a seemingly insignificant ailment was having on that very mindset.

The important lesson we’ve taken away from our experiences personally and vicariously is that these things are not terribly complex and can be easily addressed by any athlete. Why? Because it makes a difference.

Is there anything to be said for using your adrenaline at the beginning of the race to go a little faster rather than fighting it to slow down and save yourself?

Totally! Although it appears that the science on the topic is quite precise, namely that so long as the initial burst is limited to under 10 seconds, no harm is done (using type IIb, glycolytic muscle fibers that won’t be needed at slower paces).

The basis for concern enters when the excitable period exceeds that initial burst and begins to raise HR. Too high too soon risks burning through oxygen stores and forcing glycogen consumption which will most likely translate to short breath and heavy legs sooner than desired.

The point about adrenaline is the smokescreen because so long as the adrenaline is pumping, it is masking the true nature of what’s happening with that blissful feel goodyness that adrenaline provides. Then it wears off and we realize we are working a lot harder than we had intended.

Of course, that’s the extreme example. For most, it’s not likely to go that far and shouldn’t ever be a big concern. The balance only matters significantly when intending to run as close to aerobic threshold as possible (not always the case, depending on the runner and the distance).

So much wisdom in one blog post. Thanks for sharing!

…if wisdom is defined as “hard-learned lessons often still botched”… then definitely! Haha.

Thanks, Laura!